South African journalist who spurned apartheid to expose its secret masters, dies

South African journalist Hennie Serfontein was a special kind of Afrikaner because he chose to turn his back on apartheid when most whites in his country found the easier option to support it or stay silent while he covered church and society, often at great risk.

The veteran Afrikaans political journalist and documentary filmmaker often known as JHP Serfontein died peacefully in his sleep in Sandton near Johannesburg in South Africa on July 24. Serfontein was 83 years old.

Family members said his wife for 60 years was at his side.

The former journalist was best known for his exposés whilst working for South African newspapers in the mid-sixties and 1970s on the dreaded Broederbond, the secret organization of select Afrikaners who set government policy before the whites-only parliament debated it.

Serfontein once said, "There is no such thing as objectivity in journalism – but your facts have to be one hundred percent right."

He also said, "At the end of the day it is more important to follow your own conscience than to be like a sheep and follow the flock."

His patch held its dangers and the South African government of the time did not want him to report on it as he delved into the role of the churches in both supporting apartheid, and fighting it.

His daughter Anli Serfontein, who lives in Berlin and is a correspondent for Ecumenical News said, "My beloved Dad followed his conscience as an Afrikaner vehemently opposing apartheid and speaking up for the truth. He did this fully knowing how bad the backlash would be, and he never wavered."

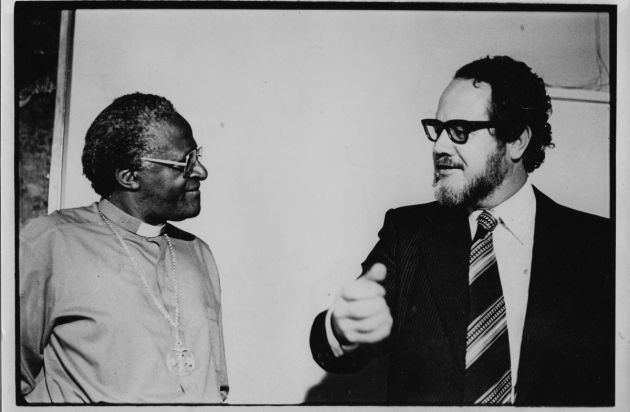

As a journalist specializing on church matters, Serfontein met Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the 1970s and had close dealings with him later as secretary-general of the South African Council of Churches.

At the time Tutu was in the forefront of non-violent resistance to apartheid in the country, before going on to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

In 1995 Serfontein made a documentary on Tutu, visiting among other things the concentration camp in Dachau to establish a link between what happened in South Africa and what happened in Nazi Germany.

RELATIONSHIP WITH BEYERS NAUDE

Serfontein's relationship with the well-known Afrikaans anti-apartheid theologian Beyers Naudé went back to the early 1950's in Pretoria when Serfontein was a student and a member of the Dutch Reformed Church which had supported apartheid.

Serfontein got into journalism in 1963 with the Broederbond exposés – the first ones were based on Naudé's documents.

Naudé was at that point still a member of the Broederbond – the ultra-secret Afrikaner organization which with its octopus-like powers that was involved in every major Cabinet and apartheid policy decision.

Because of these exposés and his friendship with Naudé, the Dutch Reformed Church refused to baptize his daughter in 1965.

Naudé founded the Christian Institute, which the government declared a banned organization in 1977, along with its founder which meant he was under virtual house arrest and unable to make contact with more than two people at a time.

For European broadcasters, Serfontein recorded and illustrated the effects of the banning order on Naudé, his total ostracization from his Afrikaner community and his belief in a non-racial society. After 1994 he also did portraits for the national broadcaster, the SABC.

The friendship with Naudé was one of the most important one's in his life, spanning five decades.

Serfontein's last broadcast for IKON in 1995 was then also aptly a profile on Naudé.

NICO SMITH

There are also unique footage of another anti-apartheid theologian, former University of Stellenbosch professor, Nico Smith a Dutch Reformed pastor who had moved to the black Mamelodi township in 1987 where he was a pastor, to live among the people he was serving.

Another important aspect was recording and exposing the heartbreak caused by the stance of the Afrikaans churches to justify apartheid on the basis of the Bible and the reaction of the international Reformed church body which in 1982 in Ottawa declared that apartheid is a heresy.

In in the late 1970s and 1980s Serfontien became a correspondent for the Dutch daily newspaper Trouw and the Swedish daily Svenska Dagbladet.

He also produced films for several TV stations in The Netherlands – IKON, NCRV, VARA at a time when Dutch journalists were often refused visas to enter South Africa.

JHP (Hennie) Serfontein spent his formative years in Pretoria in the heart of conservative Nationalist Afrikanerdom.

He was head boy of the prestigious Afrikaans Hoer Skool in Pretoria.

He was also a leadership contemporary of the last apartheid president FW de Klerk and his Foreign Minister Pik Botha in the Nationalist Party Youth organisations, before turning his back on what could have been a brilliant political career and opting for journalism and exposing apartheid.

Working for the (Johannesburg) Sunday Times, in the late sixties and early seventies, he made his name in his sensational exposés of the Broederbond as it was for the first time exposed to the full glare of publicity.

For years Serfontein was acknowledged as the foremost writer on the National Party and Afrikaner affairs in the liberal English press. For this he was branded a traitor to the Afrikaner cause and he and his family were ostracized from the Afrikaner community.

In 2015 he explained, "I'm not a church person, but I took my decision that apartheid is against the Word of God full-stop."

Throughout his life he was a close confidante of Beyers Naudé whom he first met in 1950 as a student and their opposition to apartheid followed the same path as of the 1960's when they often consulted each other.