Christianity increasingly seen as 'bad for society,' US study finds

A decades-old trend that Christianity is irrelevant is increasingly giving way to the notion that it is bad for society, a new study by the Barna Group in the United States has found.

The study found that U.S. society is undergoing a change of mind about the way religion and people of faith intersect with public life.

That is, there are intensifying perceptions that faith is at the root of a vast number of societal ills.

"Though it remains the nation's most dominant religion, Christianity faces significant headwind in the court of public opinion," says the study in it finding that Christianity is increasingly seen as bad for society.

The new major study conducted by Barna Group, is explored in the new book Good Faith, co-authored by its president David Kinnaman and released Feb. 23.

It examines society's current perceptions of faith and Christianity.

"In sum, faith and religion and Christianity are viewed by millions of adults to be extremist," the study says.

It finds the following notions that explain an emerging reality:

● Adults and especially non-believers are concerned about religious extremism.

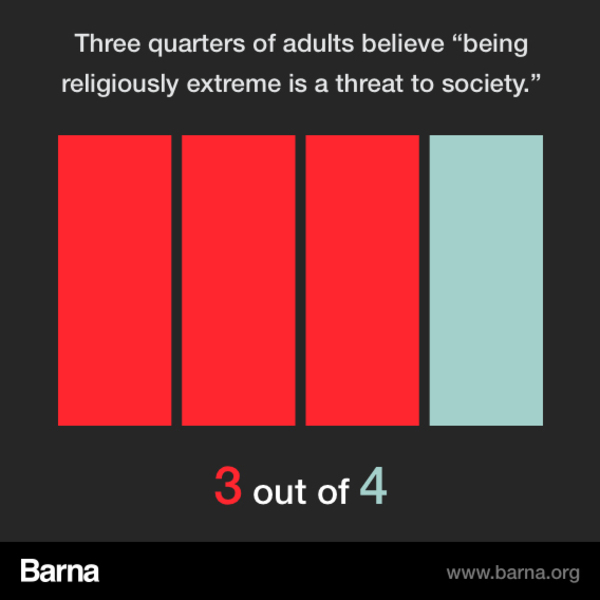

(The report note that following religiously motivated terrorism such as the recent incidents in San Bernardino and Paris - it is no wonder that a backlash against extremism is reaching a boiling point. Currently, a strong majority of adults believe "being religiously extreme is a threat to society." Three-quarters of all Americans - and nine out of ten Americans with no faith affiliation - agree with this statement.)

● Nearly half of non-religious adults perceive Christianity to be extremist.

(The perception that the Christian faith is extreme is now firmly entrenched among non-Christians in the United States. A full 45 percent of atheists, agnostics, and religiously unaffiliated in America agree with the statement "Christianity is extremist." Almost as troubling is the fact that only 14 percent of atheists and agnostics strongly disagree that Christianity is extremist. The remaining four in ten (41 percent) disagree only somewhat. So even non-Christians who are reluctant to fully label Christianity as extremist, still harbor some hesitations and negative perceptions toward the religion.

● The range of what constitutes extremism is broad, ranging from behaviors that are almost universally condemned to more narrowly defined extremism.

(What actions and beliefs, exactly, come to mind when people think about religious extremism? The researchers examined more than 20 different activities and beliefs, asking a random, representative sample of U.S. adults to identify the degree to which each of those activities appeared extreme.

● Evangelicals stand out from the norm in terms of their attitudes on religious extremism – and they exhibit major differences from the skeptics.

The research points out a massive gap between two "super segments" in American life today: evangelicals and skeptics (those who self-identify as atheist, agnostic and religiously unaffiliated).

On virtually all of the extremist factors assessed in the research, evangelicals and skeptics maintain widely divergent points of view.

For example, only 1 percent of evangelicals believe it is religiously extreme for a person to teach his or her children that same-sex relationships are morally wrong.

However, three-quarters of skeptics (75 percent) believe this is extremist.

Kinnaman comments that, "These gaps show the challenges practicing Christians and especially evangelicals are facing.

"In a religiously plural and divisive society, various 'tribes' - ranging from faithful to skeptic - are vying to decide how faith should work.

"The most contentious issues are the ways in which religious conviction gets expressed publicly, but the findings illustrate that a wide range of actions, even beliefs, are now viewed as extremist by large chunks of the population."

Kinnaman notes, "The research starkly demonstrates the ways in which evangelicals and many practicing Catholics are out of the cultural mainstream.

"In fact, skeptics and religiously unaffiliated are now much closer to the cultural 'norm' than are religious conservatives. In other words, the secular point of view, which says faith should be kept out of the public domain, is much closer to the mainstream in U.S. life."

The Barna president says this explains why millions of devout Christians are undergoing such frustration and concern as they feel out of step with social norms and the cultural momentum.

"This is most significantly felt when it comes to social views, such as evangelicals' convictions on same-sex relationships. However, the perception of 'social extremism' also applies to many other beliefs and practices, including personal evangelism and missions work."