Tutu's violence claim not true says South African government

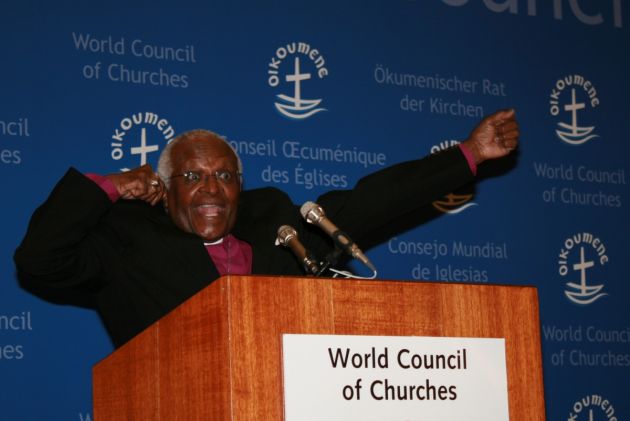

Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu is used to stirring controversy in his native South Africa, where he was a thorn in the side of the apartheid regime earning the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts in 1984.

After speaking at a ceremony last week at a ceremony in Cape Town to celebrate winning the Templeton Prize in 2103, the former Anglican archbishop of Cape Town earned criticism from the current government for his comments, which also stirred support for him

The Cabinet of South African President Jacob Zuma dismissed claims made by Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu that South Africa is one of the most violent nations.

"Research has confirmed that people in South Africa are feeling safer now than during the apartheid days," said acting Cabinet spokesperson Phumla Williams on Sunday.

"This is a direct result of the implementation of the policies and strategies by the South African Police Service. These include high police visibility and swift responses to criminal activities."

Tutu had said Thursday that South Africa has become one of the most violent societies on earth and its citizens need to face up to changes that have taken place since apartheid and regain its spirit of compassion.

"Very simply, we are aware we've become one of the most violent societies. It's not what we were, even under apartheid," Tutu said at a ceremony in Cape Town to celebrate winning the Templeton Prize.

The 81-year-old peace campaigner won the $1.7 million prize for his life-long work in advancing spiritual principles such as love and forgiveness to help to liberate people around the world, the John Templeton Foundation said on April 4.

During the last three decades of the 20th century he campaigned vigorously against South Africa's racist ideology, but showed compassion to both sides in the struggle.

"We can't pretend we have remained at the same heights and that's why I say please, for goodness sake, recover the spirit that made us great."

Cabinet spokesperson Williams said that according to police statistics, the level of violent crimes in the country has dropped significantly.

"Archbishop Tutu should be acknowledging the strides that government has made since the attainment of democracy, and also encourage religious leaders and other key stakeholders to work with government in combating crime," she said.

Williams added that the justice, crime prevention and security cluster ministers signed an agreement with President Jacob Zuma in 2010, to help ensure all South African's feel safe.

Springing to Tutu's defense Sunday was one of his successors as Anglican leader in southern Africa, Rev. Thabo Makgoba, the Archbishop of Cape Town. He wrote an opinion piece for South Africa's Independent Newspapers in support of Tutu's unstinting quest for forgiveness, quoting the late South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani:

"What we need in South Africa is for egos to be suppressed in favour of peace. We need to create a new breed of South Africans who love their country and love everybody, irrespective of their colour," wrote Makgoba, who also cut his theological teeth in the struggle against apartheid.

The Archbishop of Cape Town likened the Templeton Prize to a "spiritual Nobel"

Makgoba referred to some of the controversy since the death of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher whom he said in mostly remembered in South Africa for calling South Africa's now ruling African National Congress party as a "typical terrorist organisation" during the apartheid era.

"Stirring up strong emotions is one thing, but I was shocked to hear of parties organised to celebrate her death – and was glad these were condemned even by her strongest political opponents.

"It's not that we must uncritically 'love' all that Thatcher was and did. But it helps no-one if we dehumanise those with whom we disagree.

"The Arch [as Tutu is popularly referred to as in South Africa] has often told us that we must not reduce others to 'monsters', however awful their actions: first, because it actually makes them less responsible for their actions, and second, because it denies the possibility of redemptive hope," wrote Makgoba.

He added that accepting the existence of redemptive hope everywhere enables people to "deal with life honestly, maturely, constructively, and rationally" as the Templeton Prize supports.